Pedro Álvares Cabral

| Pedro Álvares Cabral | |

|---|---|

19th Century lithograph depicting Pedro Álvares Cabral in plate armour. There are no known authentic portraits of Cabral from his lifetime.[1] |

|

| Born | 1467 (possibly as late as 1468) Belmonte, Portugal |

| Died | 1520 (aged 52 or 53) Santarém, Portugal |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Other names | Pero Álvares Cabral Pedr'Álváres Cabral Pedrálvares Cabral Pedraluarez Cabral |

| Occupation | Fleet commander for the Kingdom of Portugal |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Spouse | Isabel de Castro |

Pedro Álvares Cabral (c. 1467 or 1468 – c. 1520; Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpeðɾu ˈaɫvɐɾɨʃ kɐˈβɾaɫ] (European) or [ˈpedɾu ˈawvaɾiʃ kaˈbɾaw] (Brazilian)) was a Portuguese noble, military commander, navigator and explorer. Cabral is generally regarded as the European discoverer of Brazil.

Contents |

Early life

Little can be said for certain regarding Cabral's life before, or after, his voyage which led to the discovery of Brazil. He was born in 1467 or 1468—the former year being the more likely[2][3]—at Belmonte, about 20 miles (32 km) from present-day Covilhã in northern Portugal.[2][4][5][6] He was born to Fernão Álvares Cabral and Isabel Gouveia, one of five boys and six girls in the family.[5][2][7] Cabral was christened Pedro Álvares de Gouveia[8] and only later—supposedly upon his elder brother's death in 1503[9][10][11]—did he switch to using his mother's surname instead of his father's.[12][13][14][15] The coat of arms of his family was drawn with two purple goats on a field of silver. Purple represented fidelity, and the goats were derived from the family's name (cabral means goats in English).[2] However, he did not employ the family's coat of arms since they were reserved exclusively for use by his elder brother.[16]

Family lore said that the Cabrais were descendants of Caranus, the legendary first king of Macedonia. Caranus was, in turn, the supposed 7th-generation scion of the demigod Hercules.[17] Myths aside, the historian McClymont believes that another family tale might hold clues to the true origin of Cabral's family. According to that tradition, the Cabraes derive from a Castilian clan named the Cabreiras, which also bore a similar coat of arms.[18] What is certain is that the family rose to prominence during the 14th century. Around 1383, Álvaro Gil Cabral (Cabral's great-great-grandfather and a military commander on the frontier) was one of the few Portuguese nobles to remain loyal to Dom João I, King of Portugal during his war against the Castilian king. As a reward, João I presented Álvaro Gil with the hereditary fiefdom of Belmonte.[2][19][20]

Raised as a member of the lower nobility,[21][22] at around age 12 Cabral was sent to the court of King Dom Afonso V in 1479, where he received an education in the humanities and learned to bear arms and fight.[23] On 30 June 1484, when he would have been around age 17, he was named moço fidalgo (a minor title then commonly given to young nobles) by King Dom João II.[24] Records of his deeds prior 1500 are very fragmentary, but there is a possibility that Cabral may have campaigned in in North Africa, as did his ancestors and as was common among other young nobles of his day.[25][26][27] On 12 April 1497, King Dom Manuel I (who had acceded to the throne two years previously) awarded him an annual allowance worth 30,000 reais.[28][29] He was concurrently given the title fidalgo in the King's council and was named a Knight of the Order of Christ.[29] There is no contemporary image or physical description of Cabral. All that has been discovered, from analysis of his remains, was that he was as tall as his 1.90 meters (6 ft 2.8 in)[30] father.[31][32]

Discovery of Brazil

Fleet Commander-in-Chief

On 15 February 1500, Cabral was appointed Capitão-mor (literally Major-Captain, or Commander-in-Chief) of a fleet sailing for India.[33][34][35] It was the custom during those times for the Portuguese Crown to appoint nobles to naval and military commands, regardless of experience or professional competence.[36] This was the case for the captains of the ships under Cabral's command—most were nobles like him.[37] The practice had obvious detrimental effects, since authority could as easily be given to highly incompetent and unfitted people, as it could fall to natural and brilliant leaders such as Afonso de Albuquerque or Dom João de Castro.[38] He has been described as well learned, corteous,[39] prudent,[40] generous, tolerant with enemies,[41] humble and with strong build,[42] but vain[43] and all too worried with the due respect to his honor and also to hierarchy.[44]

We have only the barest outline of the criteria used in selecting Cabral. In the royal decree naming him commander-in-chief, the only reasons given are "merits and services". Nothing more is known about these qualifications.[45] Historian William Greenlee argued that King Manuel I "had undoubtedly known him well at court". That, along with the "standing of the Cabral family, their unquestioned loyalty to the Crown, the personal appearance of Cabral, and the ability which he had shown at court and in the council were important factors".[46] Also in his favor may have been the influence of two of his brothers who sat on the King's council.[47] Since there was "much intrigue and jealousy" at court, Cabral may have been part of a "faction which aided his choice".[48] That conjecture is shared by historian Newitt, who said that "his appointment was a deliberate attempt to balance the interests of rival factions of noble families, for he appears to have no other quality to recommend him and no known experience in commanding major expeditions".[49]

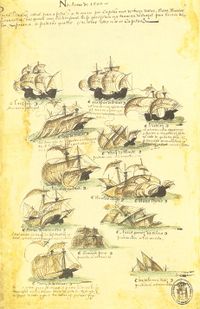

Cabral became the military chief, while other, far more experienced navigators were supposed to aid him in naval matters.[50] The most important of these were Bartolomeu Dias, Diogo Dias and Nicolau Coelho.[51][52][53] They would, along with the other captains, command 13 ships.[54][55][56] and 1,500 men.[57][58][59][60] Of this contingent, 700 were soldiers, although most were simple commoners who had no training or previously experience in combat.[61]

Arrival in a new land

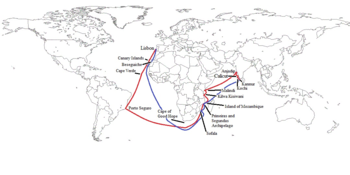

The fleet had two divisions. The first division was composed of nine naus (carracks) and two round caravels, and was headed to Calicut (or Kozhikode) in India, with the goal of establishing trade relations and a factory (trading post). The second division, consisting of one nau and one round caravel, set sail for the port of Sofala in what is today Mozambique.[62] In exchange for leading the fleet, Cabral was entitled to 10,000 cruzados (an old Portuguese currency equivalent to approximately 35kg of gold) and the right to purchase, at his own expense, 30 tons of pepper for transport back to Europe for tax-free sale to the Portuguese Crown.[63] He was also allowed to import 10 boxes of any other kind of spice, duty-free.[63] Although the voyage was extremely hazardous, Cabral would become a very rich man if he returned safely to Portugal with the cargo. Spices were then rare in Europe and keenly sought goods.[63]

An earlier fleet was first to reach India by circumnavigating Africa. That expedition had been led by Vasco da Gama and returned to Portugal in 1499.[64] For decades Portugal had been searching for an alternate route to the East to bypass the Mediterranean Sea, which was under the control of the Italian Maritime Republics and the Ottoman Empire. Portugal's expansionism would lead first to a route to India, and later to worldwide colonization. A desire to spread Christianity (or more precisely, Catholicism) to pagan lands was one factor motivating their exploration. There also was a long tradition of resisting Muslims stemming from Portugal's fight for nationhood against the Moors, which expanded to North Africa and eventually to the Indian subcontinent. Another factor galvanizing the explorers was the search for the mythical Prester John, a powerful Christian king with whom an alliance against the Muslims could be forged. Last, but not least, the Portuguese Crown sought a share in the lucrative West African trade in slaves and gold, and India's spice trade.[65]

On 9 March 1500[66][67][68] at noon, the fleet under the command of the 32 or 33-year old Cabral departed from Lisbon.[69][70] The previous day they had been given a public send-off which included a mass and celebrations attended by the King, his court and a huge crowd. On the morning of 14 March the flotilla passed Gran Canaria, the largest island in the Canary Islands.[71][72] From there, it went on to Cape Verde, a Portuguese colony situated on the West African coast, which was reached on 22 March.[73][74] The next day, a nau led by Vasco de Ataíde with 150 men disappeared without a trace.[75][76] The Equator was crossed on 9 April, and the fleet sailed westward as far as possible from the African continent in what was known as the volta do mar (literally "turn of the sea") navigational technique.[77] Seaweed was sighted on 21 April, which led the sailors to believe that they were nearing the coast. They were proven right the next afternoon, Wednesday 22 April 1500, when the fleet anchored near what Cabral christened the Monte Pascoal ("Easter Mount", as it was Easter week), located on the northeast coast of present-day Brazil.[78][79][80]

Island of the True Cross

On 23 April, all ships' captains gathered aboard the Cabral's lead ship after the Portuguese detected inhabitants on shore.[81] Cabral ordered Nicolau Coelho (a captain who had experience from Vasco da Gama's voyage to India) to go ashore and make contact. He set foot on land, where he exchanged gifts with the indigenous people.[82] After Coelho returned, Cabral took the fleet north, where after traveling 65 kilometres (40 mi) along the coast, it anchored on 24 April in what the commander-in-chief named Porto Seguro (Safe Port).[83] The place was a natural harbor, and Afonso Lopes (pilot of the lead ship) brought two natives aboard to confer with Cabral.[84]

As in the first contact, the meeting was friendly and Cabral presented them with gifts.[85] The inhabitants were stone age hunter-gatherers, whom the Europeans would generically call "Indians". The men collected food through hunting, fishing and foraging, and the women engaged in small-scale farming. They were divided into countless rival tribes.[86] Some of the tribes were nomadic and others sedentary, having a knowledge of fire but not metalworking. A few tribes engaged in cannibalism.[87] On 26 April, as more and more curious and friendly natives appeared, Cabral ordered his men to build an altar inland where a Christian mass was held—the first celebrated in the land that would later become known as Brazil. He, along with the ships' crews, participated.[88]

The following days were spent stockpiling water, food, wood and other provisions. The Portuguese also built a massive—perhaps 7 metres (23 ft) long—wooden cross. Cabral perceived that the new land lay east of the demarcation line specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas between Portugal and Spain, and was thus within the Portuguese sphere. To solemnize Portugal's claim to the land, the wood cross was erected and a second religious service held on 1 May.[89][90] In honor of the cross, Cabral named the newly-discovered land Ilha de Vera Cruz (Island of the True Cross).[91] The next day a supply-ship under the command either of Gaspar de Lemos[92][93] or André Gonçalves[94] (the sources conflict on who was sent) returned to Portugal to apprise the King of the discovery.

Tragedy in Africa

The fleet resumed its voyage on 3 May 1500[95] and sailed along the eastern South American coast where Cabral was convinced that he had met an entire continent, and not an island.[96] Around 5 May the fleet drove away and went toward Africa.[97] On 23[98] or 24[99] May "they apparently entered the high pressure area of the South Atlantic" and there "a storm suddenly overtook them, and four of the fleet sank". The exact location of disaster is not known for sure, it might have happened somewhere near the Cape of Good Hope in the sourthern tip of the African continent[100] or even "within sight of the South American coast".[101] The three naus, as well as a caravel led by Bartolomeu Dias – who had become the first European to reach the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 -, which sank claimed the life of 380 men.[102]

India and victorious return

Cabral continued to India to trade for pepper and other spices. He established a factory at Calicut, where he arrived on 13 September 1500. In Cochin and Cannanore, Cabral succeeded in making advantageous treaties. Cabral started on the return voyage on 16 January 1501, following a chain of bad luck which culminatied in a two-day bombardment of Cannanore. He arrived in Portugal with only 4 of his original 13 ships on 23 June 1501.

Later years

Fall from grace and death

Upon Cabral's return, King Manuel I began planning another fleet aimed toward India, and avenging Portuguese losses. Cabral was selected to command this "Revenge Fleet", as it was called. For eight months Cabral made all preparations,[103] but for reasons which remain uncertain, he was relieved of the command.[104] Apparently another navigator, Vicente Sodré, was to be given independent command of a section of the fleet, to which Cabral was strongly opposed.[105][106][107][108] Whether he was dismissed[109] or asked to be dismissed,[110] the result was that when the fleet departed in March 1502, its commander was Vasco da Gama—a maternal nephew of Vicente Sodré—and not Cabral.[111][112][113] It is known that "there was an active feud between the partisans of da Gama and those of Cabral, and that Cabral left the court never to return".[114] There "certainly existed a hostility between the two captains which so annoyed the king that on one occasion, when it was discussed in his presence, a partisan of da Gama was banished to Asilah (in Morocco) for life".[115]

Despite the loss of favor with Manuel I,[116][117] Cabral was able to contract an advantageous marriage in 1503[118][119] to Dona Isabel de Castro, a very rich noblewoman and descendant of King Dom Fernando I of Portugal.[120] Her mother was a sister of Afonso de Albuquerque, one of the greatest Portuguese military leaders during the Age of Discovery.[121][122][123] The couple had four children: two boys (Fernão Álvares Cabral and António Cabral) and two girls (Catarina de Castro and Guiomar de Castro).[124] There were two other daughters named Isabel and Leonor.[125] The three latter daughters entered an ecclesiastical life.[126] On 2 December 1514 Afonso de Abulquerque tried to intercede on Cabral's behalf and asked Manuel I to forgive him and allow his return to the court, to no avail.[127][128][129]

Suffering from fever and a tremor (possibly malaria) which had plagued him since his voyage,[130] Cabral withdrew to Santarém in 1509. There he spent his remaining years.[131][132] Only sketchy information is available as to his activities during that time. According to a royal letter dated 17 December 1509, Cabral had a dispute over the exchange of a property which belonged to him.[133][134] Another letter of that same year reported that he was to receive certain privileges for an undisclosed military service.[135][136] In 1818, or perhaps previously, he was raised from fidalgo to knight in the King's Council and was entitled to a monthly allowance of 2,437 reais.[137][138][139] This was in addition to the annual allowance granted to him in 1497, and still being paid.[140] Cabral died of unspecified causes, most probably in 1520. He was buried in "a chapel of the small church of the Convento de Graça, now the Asylo de São Antonio, in Santarém".[141][142][143][144]

Legacy

Posthumous rehabilitation

The land which would become Brazil had its first permanent Portuguese settlement—São Vicente—established in 1532 by Martim Afonso de Sousa. As the years passed, the Portuguese would slowly expand their frontiers westward, conquering more lands from indigenous Americans and Spanish. By 1750 Brazil had secured most of its present-day limits and was regarded by Portugal as the most important part of its far-flung maritime Empire. On 7 September 1822, the heir of Portuguese King Dom João VI led the independence of Brazil from Portugal and, as Dom Pedro I, became its first Emperor. During this span of nearly 300 years, Cabral's reputation—including his resting place—laid all but forgotten in the land of his birth.[145][146]

This began to change during the 1840s when Dom Pedro II, successor and son of Pedro I, sponsored research and publications through the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute dealing with Cabral's life and voyage. This was part the Emperor's ambitious larger plan to foster and strenghten a sense of nationalism among Brazil's diverse citizenry—giving them a common identity and history as residents of a unique Portuguese-speaking monarchy, surrounded by Hispanic-American Republics.[147] The mounting interest in Cabral had resulted from the rediscovery in 1838 of his resting place by the Brazilian historian Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen (later Viscount of Porto Seguro).[148][149] The complete abandonment in which Cabral's tomb was found nearly led to a diplomatic crisis between Brazil and Portugal—the latter ruled by Pedro II's eldest sister, Maria II.[150]

In 1871 the Brazilian Emperor—then on a trip to Europe—visited Cabral's gravesite and proposed an exhumation for scientific study, which was carried out in 1882.[151] In a second exhumation during 1896, an urn containing earth and bone fragments was allowed to be removed. Although his remains still lay in Portugal, the urn was eventually brought to the old Cathedral of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil on 30 December 1903.[152] Cabral has since become a national hero in Brazil.[153] In Portugal, however, he has been much overshadowed by his rival Vasco da Gama.[154][155] Historian William Greenlee argued that Cabral's exploration is important "not only because of its position in the history of geography but because of its influence on the history and economics of the period." Though he acknowledges that few voyages have "been of greater importance to posterity", he also says that "few have been less appreciated in their time."[156] Nevertheless, historian James McClymont affirmed that "Cabral's position in the history of Portuguese conquest and discovery is inexpugnable despite the supremacy of greater or more fortunate men".[157] He concluded that Cabral "will always be remembered in history as the chief, if not the first discoverer of Brazil".[158]

Intentional discovery hypothesis

A controversy that has occupied scholars for more than a century concerns whether Cabral's discovery was by chance or intentional. If the latter was the case, that would mean that the Portuguese had at least some hint that a land existed to the west. The matter was first raised by Emperor Pedro II in 1854, when in a session of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute he asked if the discovery might have been intentional.[159]

Until the 1854 conference, the widespread presumption was that the discovery had been an accident. Early works on the subject supported this view, including História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia (History of the Discovery and Conquest of India, published in 1541) by Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, Décadas da Ásia (Decades of Asia, 1552) by João de Barros, Crônicas do Felicíssimo Rei D. Manuel (Chronicles of the most fortunate D. Manuel, 1558) by Damião de Góis, Lendas da Índia (Legends of India, 1561) by Gaspar Correia,[160] História do Brasil (History of Brazil, 1627) by friar Vicente do Salvador and História da América Portuguesa (History of Portuguese America, 1730) by Sebastião da Rocha Pita.[161]

The first work to advocate the idea of intentionality was published in 1854 by Joaquim Noberto de Sousa e Silva, after Pedro II opened the debate.[162] Since then, several scholars have subscribed to that view, including Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen,[163] Capistrano de Abreu,[164] Pedro Calmon,[165] Fábio Ramos[166] and Mário Barata.[167] Historian Hélio Vianna affirmed that "although there are signs of the intentionality" in Cabral's discovery, "based mainly in the knowledge or previous suspicion of the existence of lands at the edge of the South Atlantic", there are no irrefutable proofs to support it.[168] This opinion is also shared by historian Thomas Skidmore.[169] The debate on whether it was a deliberate voyage of discovery or not is considered "irrelevant" by historian Charles R. Boxer.[170] Historian Anthony Smith concludes that the conflicting contentions will "probably never be resolved".[171]

Forerunners

Cabral was not the first European to stumble upon areas of present-day Brazil, not to mention other parts of South America. Roman coins have been found in today's Venezuela (northwest of Brazil), presumably from ships that were carried away by storm in ancient times.[172] Norsemen traveled to North America and even established settlements, though these ended in failure sometime before the end of the 15th century.[173] Christopher Columbus, on his third voyage to the New World in 1498, traveled through part of what would later become Venezuela.[174]

In the case of Brazil, it was once considered probable that the Portuguese navigator Duarte Pacheco Pereira had made a voyage to the Brazilian shores in 1498. However, that has long been dismissed, and is now believed that he in fact traveled to North America.[175][176][177] It is certainly known that two Spaniards, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón and Diego de Lepe, traveled along the northern coast of Brazil between January and March of 1500. Pinzón went from Fortaleza (today the capital of the Brazilian state of Ceará) to the mouth of the Amazon River. There he encountered another Spanish expedition led by Lepe, which would reach as far as the Oyapock River in March. The reason why Cabral is credited with having discovered Brazil, rather than the Spanish explorers, is because the visits by Pinzón and Lepe were cursory and had no lasting impact. Historians Capistrano de Abreu,[178] Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen,[179] Mário Barata[180] and Hélio Vianna[181] concur that the Spanish expeditions did not influence the development of what would become the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the Americas—with a unique history, culture and society which sets it apart from the Hispanic-American societies which dominate the rest of the continent.

See also

- Age of Discovery

- Exploration of Asia

- History of Brazil

- History of Portugal

- Portugal in the Age of Discovery

Bibliography

Footnotes

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 35.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Greenlee, p. xxxix.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 13.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 35.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Abramo, p. 34.

- ↑ Calmon (1981), p.42

- ↑ Espínola, p.232

- ↑ His name was spelled during his lifetime as "Pedro Álvares Cabral", "Pero Álvares Cabral", "Pedr'Álváres Cabral", "Pedrálvares Cabral", "Pedraluarez Cabral", among others. This article uses the most common spelling.

- ↑ Vieira, p.28

- ↑ Abramo, p.34

- ↑ Vainfas, p.475

- ↑ "The name used in his appointment as chief commander of the fleet for India is also Pedralvares de Gouveia." —Greenlee, p. xl.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, p. 177.

- ↑ Espínola, p.232

- ↑ Fernandes, p.53

- ↑ McClymont, p. 2.

- ↑ "According to a family tradition the Cabraes were descended from a certain Carano or Caranus, the first king of the Macedonians and the seventh in descent from Hercules. Carano had been instructed by the Delphic Oracle to place the metropolis of is new kingdom at the spot to which he would be guided by goats and when he assaulted Edissa his army followed in the wake of a flock of goats just as the Bulgarians drove cattle before them when they took Adrianople. The king accordingly chose two goats for his cognisance 1 and two goats passant gules on a field argent subsequently became the arms of the Cabraes. Herodotus knows nothing of Carano and the goats." —McClymont, p. 1.

- ↑ "A certain fidalgo who was commander of a fortress at Belmonte was with the garrison being starved into submission by investing forces. Two goats were still alive in the fortress. These were killed by order of the commander, cut into quarters and thrown to the enemy, whereupon the siege was raised as it was considered by the hostile commander that it was of no use to attempt to starve a garrison which could thus waste its provisions. It is also narrated that the son of the Castellan was taken prisoner and slain and that the horns and beards of the heraldic goats are sable as a token of mourning in consequence of this event." —McClymont, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 3.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 35.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, p. 177.

- ↑ Newitt, p. 64.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 34.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 34.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 35.

- ↑ Espínola, p.232

- ↑ Peres, p.94

- ↑ McClymont, p. 33.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Greenlee, p. xl.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 36.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 126.

- ↑ Espínola, p.231

- ↑ Diffie, p. 187.

- ↑ Peres, p.92

- ↑ Fernandes, p.53

- ↑ Boxer, p. 128.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 18.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 312.

- ↑ Espínola, p.231

- ↑ Calmon (1981), p.42

- ↑ Fernandes, p.53

- ↑ Peres, p.114

- ↑ Espínola, p.231

- ↑ Fernandes, p.52

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 34.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xli.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xli.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xli.

- ↑ Newitt, p. 65.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 37.

- ↑ Newitt, p. 65.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xlii.

- ↑ Diffie, p. 188.

- ↑ Pereira, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Newitt, p. 65.

- ↑ Espínola, p.232

- ↑ Pereira, p. 60.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 18.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, p. 175.

- ↑ Espínola, p.232

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 38.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 22.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Bueno (1998), p. 26.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 88.

- ↑ Boxer, pp. 34–41.

- ↑ Pereira, p. 64.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 18.

- ↑ Varnhagen, p. 72.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), pp. 14–17, 32–33.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 43.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 42.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 43.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 43.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 43.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 43.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 43.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 45.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 45.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 43.

- ↑ Varnhagen, p. 73.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 89.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 90.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 44.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 95.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 97.

- ↑ Boxer, pp. 98–100.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 98.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 100.

- ↑ Bueno, pp. 106–108.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 44.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 109.

- ↑ Bueno, p. 110.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xx.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 21.

- ↑ McClymont, p.21

- ↑ Bueno, p.116

- ↑ Bueno, p.116

- ↑ Bueno, p.116

- ↑ Greenlee, xx

- ↑ Bueno, p.116

- ↑ McClymont, p.23

- ↑ Bueno, p.117

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliii.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 125.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 32.

- ↑ Newitt, p. 67.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 42.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 125,

- ↑ Newitt, p.67

- ↑ McClymont, p.32

- ↑ Abramo, p. 42.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 126.

- ↑ Newitt, p. 67.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliii.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 42.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 125.

- ↑ Presser, p. 249.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 36.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, p. 177.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 3.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xlv.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xlv.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, p. 177.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 44.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 126.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, p. 177.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 42.

- ↑ McClymont, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 33.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 33.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xliv.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 44.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 33.

- ↑ Greenlee, p. xlv.

- ↑ Abramo, p. 44.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 126.

- ↑ Espínola, p.234

- ↑ Revista Trimestral de História e Geografia, p. 137.

- ↑ Vieira, pp.28–29

- ↑ Schwarcz, p. 126.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p.985

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 126.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 130.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p.985

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p.985

- ↑ Smith, p. 5.

- ↑ Alves Filho, p. 195.

- ↑ Berrini, p. 168.

- ↑ Greenlee, p.xxxiv

- ↑ McClymont, p. 36.

- ↑ McClymont, p. 36.

- ↑ Pereira, p.54

- ↑ Bueno, p.127

- ↑ Vainfas, p.183

- ↑ Bueno, p. 129.

- ↑ Bueno, p. 130.

- ↑ Bueno, p. 130.

- ↑ Calmon, p. 51.

- ↑ Ramos, p. 168.

- ↑ Barata, p. 46.

- ↑ Vianna, p. 19.

- ↑ Skidmore, p. 21.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 98.

- ↑ Smith, p. 9.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 31.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 31,

- ↑ Barata, p. 46.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 131.

- ↑ Peres, p.114

- ↑ Vianna, p. 47.

- ↑ Bueno (1998), p. 132.

- ↑ Varnhagen, p. 81.

- ↑ Barata, pp.47–48

- ↑ Vianna, p. 46.

References

- Abramo, Alcione. Grandes Personagens da Nossa História (v.1). São Paulo: Abril Cultural, 1969. (Portuguese)

- Alves Filho, João. Nordeste: estratégias para o sucesso : propostas para o desenvolvimento do Nordeste brasileiro, baseadas em experiências nacionais e internacionais de sucesso. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad Consultoria e Planejamento Editorial, 1997. ISBN 8585756489 (Portuguese)

- Barata, Mário. O descobrimento de Cabral e a formação inicial do Brasil. Coimbra: Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra, 1991. (Portuguese)

- Berrini, Beatriz. Eça de Queiroz: a ilustre casa de Ramires : cem anos. São Paulo: EDUC, 2000. ISBN 8528301982 (Portuguese)

- Boxer, Charles R.. O império marítimo português 1415–1825. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. ISBN 8535902929 (Portuguese)

- Bueno, Eduardo. A viagem do descobrimento: a verdadeira história da expedição de Cabral. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 1998. ISBN 8573022027 (Portuguese)

- Calmon, Pedro. História de D. Pedro II. 5 v. Rio de Janeiro: J. Olympio, 1975. (Portuguese)

- Calmon, Pedro. História do Brasil. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1981. (Portuguese)

- Diffie, Bailey Wallys (and Shafer, Boyd C., and Winius, George Davison). Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580 (v.1). Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1977. ISBN 0816607826 (English)

- Greenlee, William Brooks. The voyage of Pedro Álvares Cabral to Brazil and India: from contemporary documents and narratives. New Delhi: J. Jetley, 1995. (English)

- Espínola, Rodolfo. Vicente Pinzón e a descoberta do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 2001. ISBN 8574750298 (Portuguese)

- Fernandes, Astrogildo. Pedro Álvares Cabral: 500 anos. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 1969. (Portuguese)

- McClymont, James Roxbury. Pedraluarez Cabral (Pedro Alluarez de Gouvea): his progenitors, his life and his voyage to America and India. London: Strangeways & Sons, 1914. (English)

- Newitt, M. D. D. A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion 1400–1668. New York: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 041523980X (English)

- Peres, Damião. O descobrimento do Brasil: antecedentes e intencionalidade. Porto: Portucalense, 1949. (Portuguese)

- Presser, Margareth. Pequena enciclopédia para descobrir o Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Senac, 2006. ISBN 8587864742 (Portuguese)

- Revista de História ou Geografia. Issue 5. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia de J. E. S. Cabral, 1840. (Portuguese)

- Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. As barbas do Imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos. 2. Ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. ISBN 8571648379 (Portuguese)

- Smith, Anthony. Explorers of the Amazon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. ISBN 0226763374 (English)

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521646294 (English)

- Varnhagen, Francisco Adolfo de. História Geral do Brasil (v.1). 3. ed. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, N/D (Portuguese)

- Vianna, Hélio. História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república. 15. ed. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1994. (Portuguese)

- Vieira, Cláudio. A história do Brasil são outros 500. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2000. ISBN 8501057533 (Portuguese)